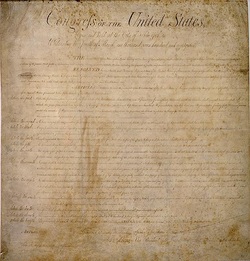

IV. Comments on the Bill of Rights

How is it that a man loses his rights? There are at least three ways; but each is a result of his own choice. First, he may agree to give them up, and if he has his wits about him, he will do that in such a way as to protect them in the process. Second, he may be deprived of them by force; which only means that he may be caused to suffer some unpleasant consequence when he attempts to use them. And third, the most subtle and effective of all, he may, by listening to the false promises of license, apply his rights and powers to evil occupations and form himself into such a creature of ignorance, bad habit, and even depravity, that he becomes incapable of the use of his most precious and most fragile faculties. Such is the dulling effect, for example, of petty thievery upon the finer senses of justice and propriety.

Throughout history men have lost the use of their unalienable rights by one or another error, but when an entire nation has moved itself from liberty toward oppression, as you are doing now, it has always been through a slackening of the public scruples, for the carelessness necessary to participation in the human vices extends both to the abuses of government officials and the vigilance of the people. Officials, drunken with authority and schemes of glory run amuck while the people, filled with the indifference born of selfish pleasures, fall asleep.

Self-government is an opportunity which must be cherished by every citizen, and if the time should come that you cease to govern yourselves, first in your own individual lives and thereafter in your political institutions, then you will be governed by others; for selfish and glory-hungry men have ever lurked about the political water holes of civilization like cunning wolves awaiting the unwary prey they are only too eager to consume in order to fill up their vanity and satisfy their lust for the regard and property of their fellows. It is precisely here that we see the requirement for the protection of the moral conscience; so let me turn your attention to the First Amendment.

Throughout history men have lost the use of their unalienable rights by one or another error, but when an entire nation has moved itself from liberty toward oppression, as you are doing now, it has always been through a slackening of the public scruples, for the carelessness necessary to participation in the human vices extends both to the abuses of government officials and the vigilance of the people. Officials, drunken with authority and schemes of glory run amuck while the people, filled with the indifference born of selfish pleasures, fall asleep.

Self-government is an opportunity which must be cherished by every citizen, and if the time should come that you cease to govern yourselves, first in your own individual lives and thereafter in your political institutions, then you will be governed by others; for selfish and glory-hungry men have ever lurked about the political water holes of civilization like cunning wolves awaiting the unwary prey they are only too eager to consume in order to fill up their vanity and satisfy their lust for the regard and property of their fellows. It is precisely here that we see the requirement for the protection of the moral conscience; so let me turn your attention to the First Amendment.

Freedom of Religion

You will notice that we placed freedom of conscience at the head of our list of rights, for we knew that if a man could not freely exercise his conscience he could not develop it fully. And a man without conscience is a man without honor. Likewise with the nation. And what is more, when the citizens fail to conduct themselves with probity, their government is required to increase its regulation of their lives; a shift of power from the people to their governors; a step from liberty toward oppression; a change eagerly assisted by ambitious politicians.

Contrary to what you have lately been told, it was our intent in the First Amendment to not only protect, but also to promote religion among the people. Not that the government should foster any particular religious philosophy (such as atheism or irreligion as it does in your schools), but that it should not discourage the development of morality and religious ethics, nor give one philosophy an advantage over another. Hence we denied the government the power to interfere in religion or to direct, control, or tax it in any way. We drew a line between them which ought not to be crossed. But that was to fortify religion, not to inhibit it! It was to protect the people from political interference in the free exercise of conscience, not to prevent the development of a moral or religious sense. To interpret the First Amendment so as to place government in opposition to religious expression in private or in public is to place government in control of religion to the extent that it can advance the philosophy of non-religion, which is in direct contradiction to the spirit of that amendment. Furthermore, it sets a free government in conflict with its own destiny, for if it should succeed in demoralizing the citizens, it will have also succeeded in its own destruction.

Our desire in this first clause of the First Amendment was to establish and protect the only enduring basis of liberty: individual self-discipline through individual rectitude. We knew that as with enterprise and art, the most effectual way the government could promote religion was to remain out of it entirely.

There are voices in the land now which attempt to twist the meaning of that law and seek to thwart all religions based upon a recognition of God. They do this because they know, and you must remember, that any human expression Which conveys belief in a Divine Creator is also a statement of the inherent worth of man, while a denial of God is a positive affirmation that man is only a well-developed beast, and may be justly reared, trained, and used as is fitting any animal. Have not millions been slaughtered under that Godless philosophy? You watched it in Russia for a half-century.

The man who will soberly reflect upon the question will soon discover that all justification for government arises in the mischievous nature of the citizen. If each one behaved justly toward others the need for civil government would vanish. There would be need for neither police nor armed forces. The poor and misfortunate would be cared for through the feelings of charity which would be released in the hearts of their fellow citizens whose just attitudes would have prepared them to share their concern and their property. In such an ideal society each mail would have complete liberty, but only because he had first made himself worthy of it by his own careful respect for the rights of others. Is it not toward that goal that you would strive if you only knew how to attain it? It is for this purpose that I have come to you: to help you find the path and give you the confidence to set upon it.

If that is your desire, then you must realize that nearly all the problems and crises of the nation have their origins in the hearts and minds of individual men, and spring from their separate but common vices. Strictly speaking, there are no social, economic, or political problems, for the conditions described in those terms are not created by society, or economics, or politics. They are, in the final analysis, created by people; the result of decisions contrived in the darkness of selfish ambition or deceit. You may consider any problem of the commonwealth, and you will discover that only a small portion is the product of circumstance aside from the human frailties. And if the difficulties arise from the people, then they are not fundamentally political or social, but moral and ethical, and there is no government institution which can solve them.

The entire nation, save a few wise men, labors under the delusion that government can make you a great country, and the result of that error is the consuming of a near third of your labor and goods in bureaus and programs which can neither comprehend nor correct the true basis of your troubles. Good government is necessary to a great nation, but it is far from sufficient.

Nay, the victories which give a nation true dignity are not won in the halls of bureaus, or in the chambers of the law, nor yet upon the battlefields of war. The struggle for national honor is fought daily in the secret heart of each citizen. It is there indeed, that the nation's decision between liberty and license is cast; it is in the heat of the fires of individual human feeling and intellect that the soul of society is forged, for the history of the commonwealth is first conceived and written in the hearts of its citizens.

I realize that all this philosophical exposition may dismay you a bit; yet I did not come to tickle your ears, but to enlighten your minds and lift your vision. I have deliberately led you to this point that I might more fully impress upon your minds the decisive import of that first clause: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof," for we founded our government upon a profound awareness of the virtues and vices of human nature. The Constitution was designed for a moral and religious people, but no government can protect a dishonorable people from the just rewards of collapse and ruin.

Our full intent was to assure each citizen the liberty of religious thought, expression, and practice in public and in private. The spiritual side of man's nature must be protected so he may freely discover the principles by which he will order his life. If he is not thus free, his morality is stunted and neither law nor popular disdain will suffice to restrain his abuse. Although the government may protect the people from political oppression, only the People can protect themselves from spiritual degeneracy, and while the former may not lead to the latter, the latter has always brought the former. The best the government can do for the preservation of liberty is to stay out of religion, and the best the people can do is to stay in it.

Contrary to what you have lately been told, it was our intent in the First Amendment to not only protect, but also to promote religion among the people. Not that the government should foster any particular religious philosophy (such as atheism or irreligion as it does in your schools), but that it should not discourage the development of morality and religious ethics, nor give one philosophy an advantage over another. Hence we denied the government the power to interfere in religion or to direct, control, or tax it in any way. We drew a line between them which ought not to be crossed. But that was to fortify religion, not to inhibit it! It was to protect the people from political interference in the free exercise of conscience, not to prevent the development of a moral or religious sense. To interpret the First Amendment so as to place government in opposition to religious expression in private or in public is to place government in control of religion to the extent that it can advance the philosophy of non-religion, which is in direct contradiction to the spirit of that amendment. Furthermore, it sets a free government in conflict with its own destiny, for if it should succeed in demoralizing the citizens, it will have also succeeded in its own destruction.

Our desire in this first clause of the First Amendment was to establish and protect the only enduring basis of liberty: individual self-discipline through individual rectitude. We knew that as with enterprise and art, the most effectual way the government could promote religion was to remain out of it entirely.

There are voices in the land now which attempt to twist the meaning of that law and seek to thwart all religions based upon a recognition of God. They do this because they know, and you must remember, that any human expression Which conveys belief in a Divine Creator is also a statement of the inherent worth of man, while a denial of God is a positive affirmation that man is only a well-developed beast, and may be justly reared, trained, and used as is fitting any animal. Have not millions been slaughtered under that Godless philosophy? You watched it in Russia for a half-century.

The man who will soberly reflect upon the question will soon discover that all justification for government arises in the mischievous nature of the citizen. If each one behaved justly toward others the need for civil government would vanish. There would be need for neither police nor armed forces. The poor and misfortunate would be cared for through the feelings of charity which would be released in the hearts of their fellow citizens whose just attitudes would have prepared them to share their concern and their property. In such an ideal society each mail would have complete liberty, but only because he had first made himself worthy of it by his own careful respect for the rights of others. Is it not toward that goal that you would strive if you only knew how to attain it? It is for this purpose that I have come to you: to help you find the path and give you the confidence to set upon it.

If that is your desire, then you must realize that nearly all the problems and crises of the nation have their origins in the hearts and minds of individual men, and spring from their separate but common vices. Strictly speaking, there are no social, economic, or political problems, for the conditions described in those terms are not created by society, or economics, or politics. They are, in the final analysis, created by people; the result of decisions contrived in the darkness of selfish ambition or deceit. You may consider any problem of the commonwealth, and you will discover that only a small portion is the product of circumstance aside from the human frailties. And if the difficulties arise from the people, then they are not fundamentally political or social, but moral and ethical, and there is no government institution which can solve them.

The entire nation, save a few wise men, labors under the delusion that government can make you a great country, and the result of that error is the consuming of a near third of your labor and goods in bureaus and programs which can neither comprehend nor correct the true basis of your troubles. Good government is necessary to a great nation, but it is far from sufficient.

Nay, the victories which give a nation true dignity are not won in the halls of bureaus, or in the chambers of the law, nor yet upon the battlefields of war. The struggle for national honor is fought daily in the secret heart of each citizen. It is there indeed, that the nation's decision between liberty and license is cast; it is in the heat of the fires of individual human feeling and intellect that the soul of society is forged, for the history of the commonwealth is first conceived and written in the hearts of its citizens.

I realize that all this philosophical exposition may dismay you a bit; yet I did not come to tickle your ears, but to enlighten your minds and lift your vision. I have deliberately led you to this point that I might more fully impress upon your minds the decisive import of that first clause: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof," for we founded our government upon a profound awareness of the virtues and vices of human nature. The Constitution was designed for a moral and religious people, but no government can protect a dishonorable people from the just rewards of collapse and ruin.

Our full intent was to assure each citizen the liberty of religious thought, expression, and practice in public and in private. The spiritual side of man's nature must be protected so he may freely discover the principles by which he will order his life. If he is not thus free, his morality is stunted and neither law nor popular disdain will suffice to restrain his abuse. Although the government may protect the people from political oppression, only the People can protect themselves from spiritual degeneracy, and while the former may not lead to the latter, the latter has always brought the former. The best the government can do for the preservation of liberty is to stay out of religion, and the best the people can do is to stay in it.

Freedom of Speech

Now I would direct your consideration to the following point: freedom of speech requires an untrammeled liberty, for as a man must be able to steal, until he has done it once, so he must be free to speak until he has shown himself an instrument of deception. That is to say, it is altogether appropriate to punish that person who has abused his liberty by deceit or slander, it is quite another matter to seek to regulate him ere he makes his utterance. In the first instance there is both reason and justice, while in the last there is a prior and therefore prejudicial encroachment upon the rights of the speaker. Furthermore, such regulations are ever subject to political manipulation; and that is precisely the nature of your so-called Fairness Doctrine which effectively (albeit indirectly) muzzles many a man who might have awakened you sooner to the true basis of your political troubles.

There are also those among you who seek to shield themselves, by an appeal to the First Amendment, in order to publish the most subtle and ruinous fraud. They, by implication (for the falsehood would never gain public acceptance were it presented directly), broadcast to a world of unsuspecting minds that immorality and even perversion are normal and necessary to the full "liberation" of mankind. But they are not normal, except to a base and morbid few, nor are they ever beneficent to the individual or his society. And what is more, they are totally foreign to the nobler side of man's nature and have always been accompanied by a return to bondage; first in a darkened and distracted mind, then in the disruption of the home, and finally in the corruption of all that is good.

If a man willfully injures the character of another he may be justly punished for libel. What then if a man publishes matter which injures the character of the entire human family by depicting man as a beast? or if he publicly promotes the deception that there is no sin between "consenting (conspiring) adults"? Should he not be held to answer for his abuse of his freedom? With your society already in alarm for its safety in the face of rising crimes of personal and intimate violence, it would be foolish indeed to tolerate those who, for profit, spread private vice in public view.

Would you allow training schools to be established throughout the land where thousands would be taught the techniques and advantages of crime? Then how long will you permit the public display of material which teaches the degenerative crimes of moral abandon? These purveyors of perversion are a blight upon the nation, for while they openly preach moral liberties, they privately seek moral anarchy.

You have only two choices: to stand and watch while they poison you and your hapless children and bring thousands into the slavery of obscene selfishness, or to enforce good local laws ("Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press") and restrain those who would corrupt the public virtue. You savor neither alternative, and in that you are right, but that is all you have. You will either stem the tide of pollution or drown therein, for the laws of human nature are as consistent and immutable as those of physical nature: obedience to them will bring social and technological progress, but the unbridled fire will ever consume.

There are also those among you who seek to shield themselves, by an appeal to the First Amendment, in order to publish the most subtle and ruinous fraud. They, by implication (for the falsehood would never gain public acceptance were it presented directly), broadcast to a world of unsuspecting minds that immorality and even perversion are normal and necessary to the full "liberation" of mankind. But they are not normal, except to a base and morbid few, nor are they ever beneficent to the individual or his society. And what is more, they are totally foreign to the nobler side of man's nature and have always been accompanied by a return to bondage; first in a darkened and distracted mind, then in the disruption of the home, and finally in the corruption of all that is good.

If a man willfully injures the character of another he may be justly punished for libel. What then if a man publishes matter which injures the character of the entire human family by depicting man as a beast? or if he publicly promotes the deception that there is no sin between "consenting (conspiring) adults"? Should he not be held to answer for his abuse of his freedom? With your society already in alarm for its safety in the face of rising crimes of personal and intimate violence, it would be foolish indeed to tolerate those who, for profit, spread private vice in public view.

Would you allow training schools to be established throughout the land where thousands would be taught the techniques and advantages of crime? Then how long will you permit the public display of material which teaches the degenerative crimes of moral abandon? These purveyors of perversion are a blight upon the nation, for while they openly preach moral liberties, they privately seek moral anarchy.

You have only two choices: to stand and watch while they poison you and your hapless children and bring thousands into the slavery of obscene selfishness, or to enforce good local laws ("Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press") and restrain those who would corrupt the public virtue. You savor neither alternative, and in that you are right, but that is all you have. You will either stem the tide of pollution or drown therein, for the laws of human nature are as consistent and immutable as those of physical nature: obedience to them will bring social and technological progress, but the unbridled fire will ever consume.

The Right to Bear Arms

The primary cause for our affirmation of the right of the people to keep and bear arms was our concern for military power: that the armed forces might need immediate and widespread assistance in repelling an aggressor, or that the citizens might find it necessary to defend themselves from oppression by their own military. We desired that every man have the right to arms.1 But there is another consideration which is based on a fundamental right and requires a little elaboration since you are in debate upon the issue.

If a man find himself or his property in peril of plant or animal, he has a manifest right to defend what is his. If he be in jeopardy of another man, he retains the same right. There can be no alternative to this principle without opening the door to all manner of legally protected plunder and personal assault. The law must either sustain this right or else it shields the criminal, for it will either tend to protect the one or the other, there being little middle ground. To protect the bad man is to encourage his ravages.

Most of the laws proposed in Congress are unenforceable upon the criminal, and worse, they are oppressive upon the citizen who is purportedly thus protected. If you wish to put an end to the wrongful use of arms, it is only necessary to make that use ill-advised, for outlaws reason also, and when the risk becomes too great, they will cease. If the beweaponed rascal were aware, for example, that the penalty was at least thirty years' imprisonment without possibility of leniency, what would be the effect? An extreme penalty, it may be thought, but it is perhaps no more unreasonable than the over-careful protection of the offender now required by your judicial system.

If a man shows disregard for the life of another, then justice demands an appropriate restriction upon his rights, otherwise equal protection under the law and the public safety must suffer.

The "shot heard round the world" was fired in defense of the arms we had cached at Concord and Lexington, hence the Second Amendment was also our statement of the right of the people to forcibly revolt when that horrible prospect is the only course by which they may reassert their unalienable rights. The powers of government are delegated to it from the people, and when a government becomes altogether inimical to their rights and wholly independent of their will, they necessarily have the right for themselves and the duty to their posterity to revolt; to remove despots from power and reestablish liberty. Reason, history, and the most recent European oppressions amply testify of the inability of the people to throw off a government which has gained control of their personal arms. They have been defenselessly driven, slain, and imprisoned within their own lands and homes. You may be profoundly grateful that you still have sufficient control of your government to return to a fullness of freedom without armed revolution. You know not how grateful.

I shall finally comment upon the last amendment in the Bill of Rights, for it is, in respect to its comprehension, the most significant because we summarized in it the essence of human rights and government and placed them in proper relationship one to another. We simply restated that fundamental principle of the rights of free men: that in the United States the federal government possesses only those powers delegated to it by the Constitution; that there are certain powers which the several States may not exercise; and all other powers whatsoever are retained by the individual citizens. For frequency of violation this Article is unsurpassed, and you will find, when you have restored the Constitution to its proper role, that the relentless disregard for this principle has brought you most of the dismay and perplexity which now afflicts you.

Now, you have noted, no doubt, that I have spoken mainly of the moral and religious aspects of your liberties. That is not because I have grown more religious with age, but because you have grown less. Liberty has always brought the blessings of abundance, and abundance has always tended to pride and a haughty disrespect for basic moral principles. If you will consider it carefully, you will see that you stand now at the crux of the nation's life: you may continue into the growing indifference of opulence and squander this Bill of Rights, or you may rise above the affluence of freedom and keep both your liberty and your wealth. You must stretch your capacities for noble character, catch the vision of a higher order of life, put yourselves in careful harmony with sound ethical doctrine, and lead a saddened but hopeful world into the fuller freedom of personal dignity. That is the true destiny of the nation. That is the dream I feel glowing in your hearts. Then believe in that dream, follow it, and work to make it real!

1 Author's note: There is a general misunderstanding that the militia mentioned in the Second Amendment refers to the National Guard or the armed forces. The correct meaning in this context is "the armed citizenry." The United States' Code, Chapter XIII, Section 311, defines the militia as all able-bodied males of 17 years' age.

If a man find himself or his property in peril of plant or animal, he has a manifest right to defend what is his. If he be in jeopardy of another man, he retains the same right. There can be no alternative to this principle without opening the door to all manner of legally protected plunder and personal assault. The law must either sustain this right or else it shields the criminal, for it will either tend to protect the one or the other, there being little middle ground. To protect the bad man is to encourage his ravages.

Most of the laws proposed in Congress are unenforceable upon the criminal, and worse, they are oppressive upon the citizen who is purportedly thus protected. If you wish to put an end to the wrongful use of arms, it is only necessary to make that use ill-advised, for outlaws reason also, and when the risk becomes too great, they will cease. If the beweaponed rascal were aware, for example, that the penalty was at least thirty years' imprisonment without possibility of leniency, what would be the effect? An extreme penalty, it may be thought, but it is perhaps no more unreasonable than the over-careful protection of the offender now required by your judicial system.

If a man shows disregard for the life of another, then justice demands an appropriate restriction upon his rights, otherwise equal protection under the law and the public safety must suffer.

The "shot heard round the world" was fired in defense of the arms we had cached at Concord and Lexington, hence the Second Amendment was also our statement of the right of the people to forcibly revolt when that horrible prospect is the only course by which they may reassert their unalienable rights. The powers of government are delegated to it from the people, and when a government becomes altogether inimical to their rights and wholly independent of their will, they necessarily have the right for themselves and the duty to their posterity to revolt; to remove despots from power and reestablish liberty. Reason, history, and the most recent European oppressions amply testify of the inability of the people to throw off a government which has gained control of their personal arms. They have been defenselessly driven, slain, and imprisoned within their own lands and homes. You may be profoundly grateful that you still have sufficient control of your government to return to a fullness of freedom without armed revolution. You know not how grateful.

I shall finally comment upon the last amendment in the Bill of Rights, for it is, in respect to its comprehension, the most significant because we summarized in it the essence of human rights and government and placed them in proper relationship one to another. We simply restated that fundamental principle of the rights of free men: that in the United States the federal government possesses only those powers delegated to it by the Constitution; that there are certain powers which the several States may not exercise; and all other powers whatsoever are retained by the individual citizens. For frequency of violation this Article is unsurpassed, and you will find, when you have restored the Constitution to its proper role, that the relentless disregard for this principle has brought you most of the dismay and perplexity which now afflicts you.

Now, you have noted, no doubt, that I have spoken mainly of the moral and religious aspects of your liberties. That is not because I have grown more religious with age, but because you have grown less. Liberty has always brought the blessings of abundance, and abundance has always tended to pride and a haughty disrespect for basic moral principles. If you will consider it carefully, you will see that you stand now at the crux of the nation's life: you may continue into the growing indifference of opulence and squander this Bill of Rights, or you may rise above the affluence of freedom and keep both your liberty and your wealth. You must stretch your capacities for noble character, catch the vision of a higher order of life, put yourselves in careful harmony with sound ethical doctrine, and lead a saddened but hopeful world into the fuller freedom of personal dignity. That is the true destiny of the nation. That is the dream I feel glowing in your hearts. Then believe in that dream, follow it, and work to make it real!

1 Author's note: There is a general misunderstanding that the militia mentioned in the Second Amendment refers to the National Guard or the armed forces. The correct meaning in this context is "the armed citizenry." The United States' Code, Chapter XIII, Section 311, defines the militia as all able-bodied males of 17 years' age.